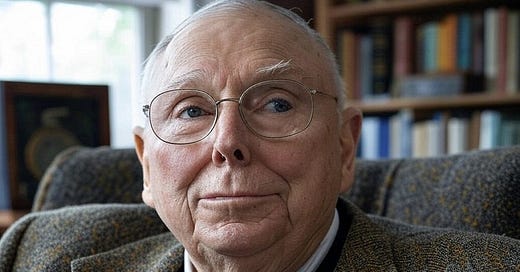

Charlie Munger’s Final Stock Market Prediction Will Make You Rethink the Next Decade.

More investors. New tech. A whole new playing field.

Charlie Munger once said:

“If I can keep my chin up after life’s kicked me in the teeth, surely you folks can weather a little volatility.”

He was the perfect example of what happens when a sharp mind and serious money meet a straight shooter who didn’t bother with sugarcoating.

To most, Munger came off as the quiet, quick-witted guy next to Buffett. But he had a spine tougher than steel.

Before becoming an investing giant, Munger took some brutal hits that would’ve knocked most people flat.

At 21, he dropped out of college to join the Army Air Corps during World War II. He ended up working as a meteorologist in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands — not exactly a dream post, but it taught him discipline in the middle of freezing, muddy nowhere.

At 31, his first marriage fell apart — a messy divorce that left him near broke and juggling custody of his kids at a time when divorce carried a heavy social weight.

His friend Roy Tolles said, “Charlie didn’t whine — he just picked up the pieces and kept going, even when the world wasn’t kind.”

Then, at 35, the real blow hit: his son Teddy was diagnosed with leukaemia and passed away at age 9 after a long, painful fight. Munger spent endless hours in hospitals, totally helpless. “It was pure hell,” he said. “And no amount of money or smarts could fix it.”

At 52, another setback — cancer took his left eye after a failed surgery. Being a lifelong bookworm, that could’ve crushed him, but instead, he just shrugged: “I’ve still got one good eye and a library to get through.”

Even with a net worth of $2.3 billion — a fraction of Buffett’s $107B — Munger still worried about the state of value investing.

“There’s too much cash out there now and too many sharp players chasing the same scraps,” he warned.

He saw it clearly — slimmer pickings, more competition, and way less room for error.

You must aspire to ‘adequate,’ not extraordinary, performance.

I first stumbled across value investing while watching one of Warren Buffett’s many interviews — the kind where he lights up talking about Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor.

At its core, the idea is simple: Buy cheap. Sell high.

Value investing is exactly what it says on the tin — a strategy made famous by Buffett and Munger, where you look for stocks trading below their worth.

The bet is that, eventually, the market will catch on.

Here’s a quick quote from Graham that sums it up nicely:

“You must thoroughly analyse a company and the soundness of its underlying businesses before you buy its stock — you must deliberately protect yourself against serious losses — you must aspire to ‘adequate,’ not extraordinary, performance.”

That’s the foundation.

But even Munger later questioned whether this approach would hold up now that the game is so crowded. Investing has gone mainstream. With a few taps on a phone or keyboard, anyone can call themselves an investor today.

Wealth management’s growth reflects that shift. More people—and pros—are trying to outsmart the market.

According to Statista, assets under management in wealth management are expected to hit $83.19 trillion by 2027. Financial advisory alone makes up $80.87 trillion, up from $57.03 trillion today.

That’s a lot of smart money chasing the same scraps.

When everyone’s smart, the edge disappears.

Munger saw it coming.

The rise of online trading didn’t just open the doors — it flooded the room.

Now, everyone has access to the same dashboards, reports, and TikToks, which explain discounted cash flow as if it were a life hack.

The result? Markets are more efficient. The low-hanging fruit is gone.

And those juicy mispriced stocks? Good luck spotting them before someone else does.

“It’s not the old days anymore,” Munger said. “You’ve got a bunch of sharp people all trying to outsmart each other — and the good stuff doesn’t stick around for long.”

He wasn’t wrong.

Value investing—the tried-and-tested Buffett/Munger playbook—hasn’t exactly been lighting up the markets over the last decade.

Meanwhile, growth stocks have surged. Think Facebook, Apple, Amazon, and Google—big, fast-moving companies that promise scale and feel like safer bets when the economy’s dragging.

A recent study broke it down using the Fama-French Three-Factor Model, which compares value stocks (cheap relative to fundamentals) against growth stocks (expensive but full of potential).

The study concluded:

“The macroeconomic backdrop over the past decade has been especially unfriendly to value. However, we believe that the worst of the crisis is now in the past, as many of the cyclical headwinds for value are turning into cyclical tailwinds. Most importantly, a significant valuation gap has now opened up between value and growth stocks. In the past, differences of this magnitude have heralded significant value outperformance over subsequent years. This suggests that betting against value over the long-term may no longer look like a tenable investment option. Nevertheless, investors should tread carefully, as certain structural disruptions mean that some companies may be “value traps”: companies that are cheap for good reason. Identifying true value stocks requires in-depth security analysis, which entails knowledge, experience and resources that cannot be easily replicated.”

Value’s had a rough run, but the tide might be turning. That said, not every cheap stock is a good one — spotting real opportunities still takes serious research and experience.

And the numbers don’t lie: Value’s been lagging for almost eight years.

The game hasn’t just changed. It’s faster, tighter, and a lot less forgiving.

Warren Buffett’s core belief about markets comes down to this one idea.

It’s that — “People never change”.

Since society started glorifying entrepreneurs and investors, I’ve been hooked on Munger and Buffett.

I love how they could disagree openly and still laugh about it. It made investing — which can be dry as hell — actually feel interesting.

Buffett once said in an interview while Munger was still alive:

“We’ve never had an argument in almost 60 years of knowing each other. We just kind of knew we were made for each other.”

But what really stuck with me was his take on opportunity: Markets are moved by people doing dumb things.

Doesn’t matter how smart someone is — the stock market is still human-driven. And humans? We’re irrational.

That’s where the edge is.

Buffett put it like this:

“Investing used to be a serious part of capitalism — now anyone can jump in. There’s been a big rise in dumb behaviour because getting money is so much easier than it used to be. You could start 15 dumb companies in the last decade and still get rich, even if none of them worked out. Back when we started, you couldn’t raise money to do the dumb stuff — thankfully.”

And that’s the wild part:

The more things change in markets, the more it reflects that people have stayed the same.

Final Thoughts

People are still running the show — and that’s where the opportunity is.

Until AI takes over the investing process, which is not too far away, human decisions will create arbitrage. This means irrational behaviour isn’t going anywhere (soon)— and neither are the opportunities it creates.

As Buffett once said,

“Regarding money, we’ll always do dumb things.”

Value investing sounds simple on paper.

Buy good stuff for less than it’s worth. But it’s rarely practised — probably because it requires two things most people struggle with: patience and an ability to judge well.

Now that Millennials and Gen Z are entering their prime earning years investing isn’t just a capitalist game anymore—it’s become mainstream. And that could lead to some serious inefficiencies.

Want proof?

Check out where Gen Z is getting their financial advice:

60% of non-pro investors rely on YouTube

Others turn to TikTok, Instagram, Twitter, Reddit, and Facebook

And 51% of Gen Z non-investors say they learn from friends or family

Clare Francis, Director of Savings and Investments at Barclays Smart Investor, says:

“Our research shows a quarter of people don’t know how or where to start investing, with growing numbers turning to social media for support. But with half not carrying out regular checks on influencers, they’re at risk of making unsuitable decisions or even falling victim to scams.”

If that doesn’t scream inefficiency, I don’t know what does.

Just 34 days shy of turning 100, Charlie Munger passed away at 99.

Buffett put it best:

“Without Charlie’s inspiration, wisdom, and involvement, Berkshire Hathaway simply wouldn’t be what it is today.”

If this blog brought you any value, I would appreciate you sharing it or upgrading your subscription.

This is all so true. For all of us it remains difficult to define "Value". Most of the metrics used are poor measures of actual value and Sentiment and Technical Factors are used more.

Oh, give it a rest … .