Kevin O’Leary: You'll Become Wealthy Without the Risk Exposure if You Understand MPT.

Steal this approach that 99% of wealth funds use, or do the opposite.

You did it again, didn’t you?

You built up some savings from your overtime over the last few months and got a juicy end-of-the-month bonus.

Now you’re contemplating what to do with it.

As Ray Dalio says, when you save, you’ll have a different conversation with yourself than the person who spends impulsively.

The next natural question you’ll ask yourself is, where do I keep the money I’ve saved?

You could:

Book another holiday.

Splash out on a new wardrobe.

Make some home improvements.

Keep it in a savings account, earning interest?

None allows you to grow your wealth over time, so you set out to scratch your investing itch.

You’re inexperienced and dive headfirst into an investment with a scattergun approach, with your emotions leading the way.

I’ll share one of my investing sins to be a good sport.

It’s what I did when I first bought Facebook stock.

I intuitively thought their ad product was underpriced, which it was.

I assumed that as more advertisers moved away from television and print and used social media advertising, Facebook (Meta) would make an increasingly large profit, which it did.

That was it, though.

I had no information on the management team.

No insights into earnings or growth potential.

No understanding of market trends.

No company financials.

No strategy.

I might as well have rolled the dice on a roulette wheel in a rundown casino.

It was beyond risky.

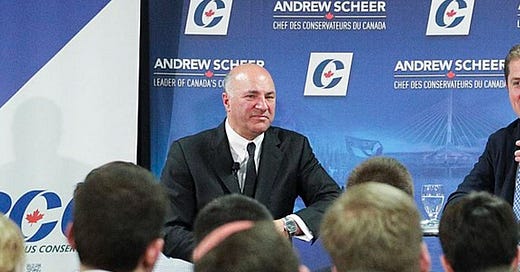

Kevin O’Leary goes by his tongue-in-cheek nickname, Mr. Wonderful.

Following season one of Shark Tank, a would-be entrepreneur tried selling him a music publishing deal; O’Leary proposed an aggressive 51% equity position to control the company, which his co-hosts saw as Militant.

So the name Mr Wonderful was born.

You see O’Leary’s softer nature when he speaks about his late mother, a skilful investor.

Georgette Booklam managed her finances meticulously, but no one knew the level of her success until after her death.

She followed a straightforward strategy, which Kevin says reduces your risk exposure and gives you a shot at wealth.

And the markets will be kinder to you.

Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT)

There’s a growing trend of entrepreneurs who cite their moms as underpinning their success.

O’Leary says the most significant lesson he learned from his mother was the basic portfolio theory of diversification.

He says that in her day, the S&P500 had only ten sectors— today, there are 11, including real estate.

The theory suggests that you should never put more than 20% in one sector and no more than 5% into a single stock.

The strategy “forces you to get diversified, and the market treats you better when you’re diversified because you never know what’s going to happen.”

American economist Harry Markowitz pioneered the theory in his paper “Portfolio Selection,” for which he won a Nobel Prize.

MPT assumes you prefer less risky investments, and with that aversion to risk, it implies you should invest in multiple asset classes to spread the uncertainty.

The expected return is on the entire performance of your diversified portfolio.

The hypothetical figures below show five equally weighted assets, the 20% Kevin’s mom suggested, and expected returns of 4,6,9,11 and 15 percent, which equals an 8.5% total portfolio return.

4% gain x 20% invested in a single sector +

6% gain x 20% invested in a single sector +

9% gain x 20% invested in a single sector +

11% gain x 20% invested in a single sector +

15% gain x 20% invested in a single sector +

= 8.5% total portfolio return.

So, if you cut out the above calculations, all it’s saying is to put your investments in several places because you never know what bad luck you’ll have.

Your view on constructing a portfolio may change when you read further.

The Oracle of Omaha Says, “It’s a load of old twaddle.”

Any strategy with the word “theory” will be on the receiving end of criticism.

Warren Buffett is brilliant at identifying the best businesses to buy.

He has a skill that many do not possess.

He’s also firmly in the camp of “concentrators.”

Buffett believes volatility does not equal risk and that “you shouldn’t be investing in more than six companies in your lifetime because very few people have ever got rich with their seventh best idea.”

You’ll be making a terrible mistake if you’re searching for a 7th business to invest your money instead of putting more money into your first.

You get more wealthy just doubling down on your first idea.

A good diversifier will always beat a bad concentrator (there’s a caveat)

Picking between concentration and diversification is a hot potato among investors.

If you pursue diversification, you may have to trade off greater risk control for less upside—something everyone understands intuitively.

Researchers in Australia ran a study on the Australian stock market and wanted to determine which strategy performed best.

They specifically wanted to compare two approaches: one in which fund managers diversified their investments and the other in which they concentrated much of their money into fewer stocks.

The Aussie researchers looked at how much money each strategy made over time.

They also measured an “information ratio,” similar to a Sharpe ratio, an investment’s risk-adjusted returns. i.e., how much risk vs. reward does this investment give me?

The higher the information ratio, the better the risk-adjusted returns and the better the investment.

The researchers found that concentrated investments in a smaller stock pool outperformed diversification — every time.

Fund managers who invested heavily in a few stocks they hand-picked faired better than when they diversified their investments.

It led to higher profits even when considering the risk factor of potentially more significant losses.

The researchers concluded that there were two significant factors in the success of concentrated investing.

It was the joint impact of these two decisions.

Stock selection

Portfolio construction

In other words, could you pick the right stocks?

Could you combine your small group of stocks to form an investment portfolio, investing the right amount of money in each to maximise your profits?

When I was greener than an Amazon rainforest putting my hard-earned mullah into Facebook stock, I’m not sure I could’ve got this right.

The table below shows different-sized portfolios.

The top 5, top 10, and so on relate to the hand-selected stock each fund manager was most confident in.

It also shows how each pool of stocks performed relative to their entire fund and the index.

The “excess return” of the “top 5” conviction-weighted portfolio was 3.75%, which means it made 3.75% more than the manager’s own fund.

The “top 5” again made a 5.26% excess return compared to the general index.

As you go down the chart and the stocks get less concentrated, the performance continues to decline.

The “tracking error” is just fancy for volatility, which is higher the more concentrated the stocks.

So you take the excess return and divide it by the tracking error, which gives you the “information ratio,” the risk-adjusted return (similar to a Sharpe ratio).

The higher the “information ratio” figure, the better the stock’s performance relative to risk.

The table shows how well the fund managers’ confidence in their investment choices paid off.

Concentration was the winner — every time.

Final thoughts

Kevin O’Leary made a lousy investment in the now-defunct crypto exchange FTX, losing about $9.7 million after the founder, Sam Bankrupt Fried, ran off with the money.

It’s an example of where diversification saved O’Leary.

But it digs into a more profound question.

Does diversification protect you against the unknowns, and if it’s unknown, do you have any right to invest and expect a positive outcome?

“Diversifying in practice makes very little sense to someone who knows what they’re doing.

Diversification is a protection against ignorance.

If you want to ensure nothing bad happens to you relative to the market, there’s nothing wrong with that for someone who feels they don’t know how to analyse businesses.

If you know how to value and analyse businesses, it’s crazy to own 40 stocks.

Putting money in number 30 or 35 on your list of attractiveness and foregoing putting more money into number one just strikes Charlie and me as madness”.

It all ultimately comes down to who you are.

If you’re unwilling to read up on individual companies regularly, investing in an ETF, Mutual fund, or Index or spreading your investments out will protect you against a lack of knowledge.

Buffett says the “know-something investor” who enjoys staying up to date with their investments should leverage their knowledge to achieve above-market returns.

It’s an approach I agree with.

I’ve said this for a long time. Pick a couple horses and feed them really well. They’ll win sometimes and they’ll consistently place. Audit them 1/4LY. Adjust only when necessary. I’m a greenhorn investor though so I’ll defer to the pros.