Tim Draper: If You Understand the Adoption Curve, You’ll Become Wealthy.

The key indicator is the false start.

Hey everyone, sorry for the delay—yesterday was my birthday, and I spent some quality family time enjoying a rare sunny day here in the UK. So, here's yesterday's blog. If you enjoy it, please give it a share. It's how we grow. Thanks!

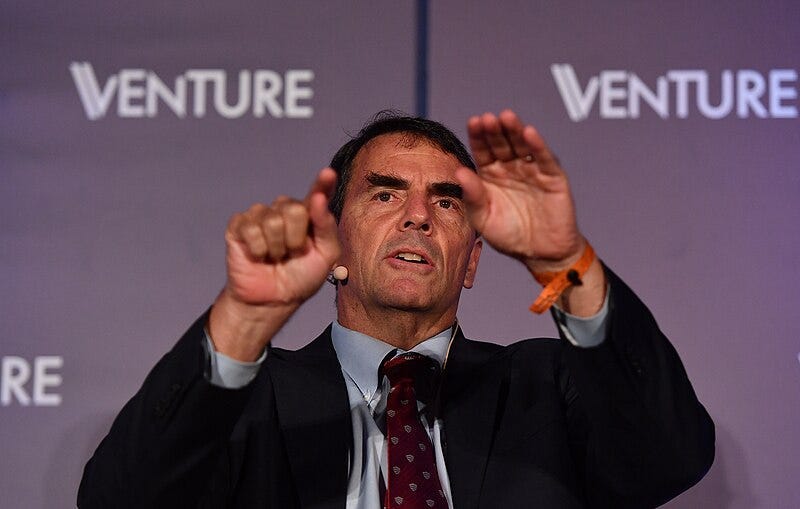

Tim Draper is a celebrated venture capitalist who says one of his biggest failures was passing on Google, Yahoo, and Facebook.

T. Draper — “Everyone thinks, ooh, you lose money — no, it’s failure to act.I missed out on 10,000 times my money with Google, and the $ 115 million into Facebook would be worth $300 billion — oops.”

I first heard about this unconventional visionary on the Anthony Pompliano show. He talked about the time he dropped $19 million on 30,000 Bitcoins — seized from the Silk Road marketplace by US Marshals, and everyone in traditional finance thought he was nuts.

When I listen to him speak, it feels like he’s got a sixth sense for spotting trends, but he always adds a caveat when he talks about these winners — “If you use my strategy, you must be willing to fail a lot.”

Draper puts it simply — “The hardest investments to make are usually the ones that pay off big.”

One investment was so outlandish eight out of ten partners at his firm, Draper Fisher Jurvetson, were against it.

Investing in an American car company seemed like a crazy idea, but Tim Draper talked the firm into it. They agreed, saying, “Alright, but let’s not go too big on the investment.”

It was Tesla’s $40 million Series C round just four months before Elon’s company went public in 2006. Draper admits they got a 30x return from it, but it could have been an eye-watering 1000x if he hadn’t sold too early.

It’s like I keep hearing on X, “No one goes broke taking profit”.

Backing an unproven concept is tough, but before investing, TD always asks himself, “What could the world look like? And is that a world I want to live in?”

He tells the difference between a fleeting narrative and something truly innovative by asking the founder one simple question:

“Why are you doing what you’re doing?”

Their answer tells him if the company has the potential to break into the world. It helps him filter out entrepreneurs who aren’t working on something transformative for humanity.

If there’s a deep desire to “change the world” and make it better for the customer, and there’s a big enough market for it, those factors make him dive in “hoping to catch a wave.”

I’ve always been fascinated by how top investors manage to hit winners as if they were playing with a stacked deck. Now, before you launch a full-scale assault in the comments with, “But Jay, these guys get the insider loop before anyone else”, let’s look at the success rate.

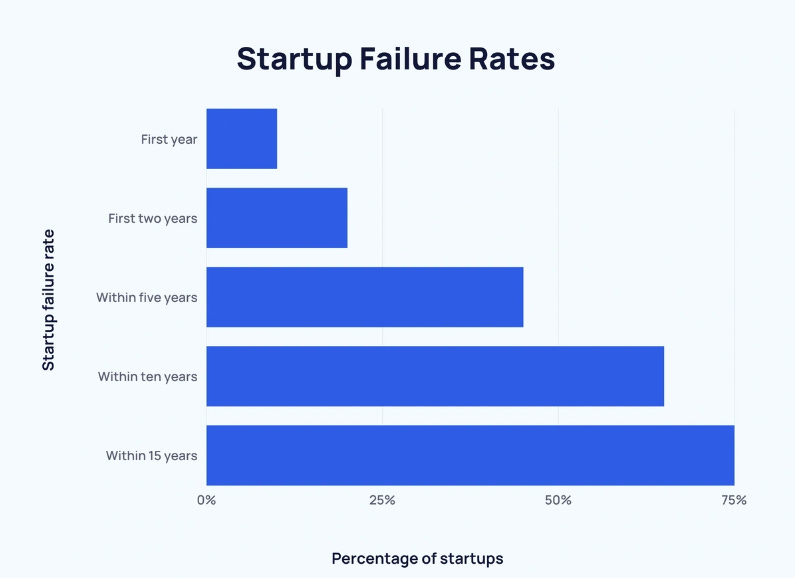

According to data, 90% of start-ups in America fail — 6,581 of the 8,775 financial tech firms backed by venture capitalists like Draper fail. That’s a 75% failure rate.

Out of the 2,194 remaining, only 20 achieve revenues of $100 million, putting your odds of landing a household name investment at just 0.22%. Not great.

It proves just how sharp Draper is — it kinda makes me want to tip my hat to him.

His early-stage investment list reads like a hitlist of tech titans: Skype, Tesla, SpaceX, SolarCity, Ring, Twitter, Twitch, DocuSign, Coinbase, Robinhood, and Hotmail.

Security would march you out of the casino if you had this many wins at the poker table.

A Winning Formula Has Its Method.

It’s not luck.

I’m always fascinated by how top investors, while not business operators, have this ability to understand companies.

It’s like Warren Buffett says: “I’m a better investor because I’m a businessman and a better businessman because I’m an investor.”

They come hand in hand.

TD pulled off a smooth trick to supercharge Hotmail, which was one of his early gambles. By slapping a signup invite on every outgoing email, Hotmail exploded with millions of users. It put Draper on the map as the mastermind behind viral email marketing.

Searching for efficiency is hardwired in him — but it’s the founder or team that is at the top of the hierarchy when it comes to investing because you’re betting on their ability to execute.

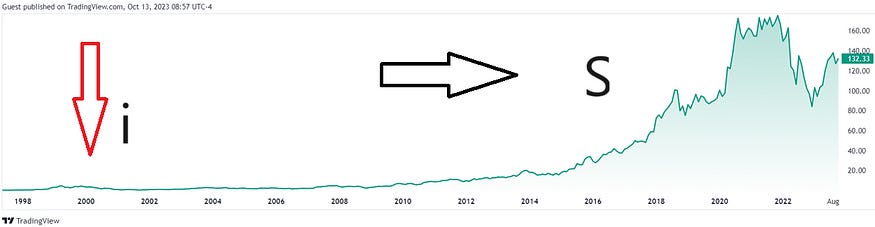

Once Draper’s happy with the founder and ‘market fit’, there’s one more key ingredient. He calls it the “Draper I-S curve” and says new technologies follow the same trajectory:

“Initial hype, a subsequent downturn, gradual improvement, and eventual widespread adoption.”

Understanding this pattern really gives you an edge, especially if you focus on the space between the “i” and the “s” on a price chart. It’s like having insider knowledge.

For me, this was a genuine aha moment.

Opportunity often comes to the second mover.

Draper’s central tenet for investing is “The earlier you get in, the more uncertainty there is, but the higher your upside”.

Getting in early doesn’t mean you need to be first.

Diving into new tech can often feel like a false start — everyone sees its big potential, but making it user-friendly takes extra elbow grease. That’s where you shine as an investor.

The sweet spot for investing? Right after the stumble, when the idea’s solid but hasn’t blown up yet. That’s your queue to jump in with your finger hovering over the buy button.

Mainstream media inevitably pigeonholes said new technology as a “trend for kids” or, as they called the Internet in 2000, “just a passing fad.”

Tim Draper — Source

“Almost every technology goes through the I-S curve, every industry comes up, gets hyped to the max, and that’s the dot on the “i”, so think of a cursive i.

And then it drops, and people complain about why it’s not good, like the Internet in its early inception. So, for years, it sits there languishing.

While that’s happening, all these great engineers are working hard and coming up with great ways for us to experience this internet thing. It slowly creeps up like an S, then explodes for years”.

Final thoughts

What stands out to me is although Tim Draper is incredibly early, he’s never the earliest or “the first man in”.

So he’s not guessing.

He waits for the dot on the “i” and then observes how founders and engineers build these products. Then, reacts to something that has already happened and takes advantage of it.

Amazon’s market cap rose from around $100 million in its first bull run during the dot-com bubble in 2000 to over $1.3 trillion today. That’s an increase of 1.3 million per cent (1,300,000%).

If you had done your homework on Jeff Bezos company, you still would’ve had 14 years from its market low to invest in Amazon before it took off like a missile.

If you’re in the US, the average paycheck after taxes is $3,200. Let’s say you had put a month’s salary into Amazon 13 years after the dot-com crash. You’d be looking at a 1048.20% return and a $33,542 profit.

They’re not the only ones with parabolic price rises after a lengthy languishing period. Take Apple, Facebook, Google, and Netflix.

We had a lifetime to invest before it was “too late.”